About the project

This website is about my parents’ lives in Laos. Since they never sat me down and told me their story, I asked them to sit down and tell me and share it with the world.

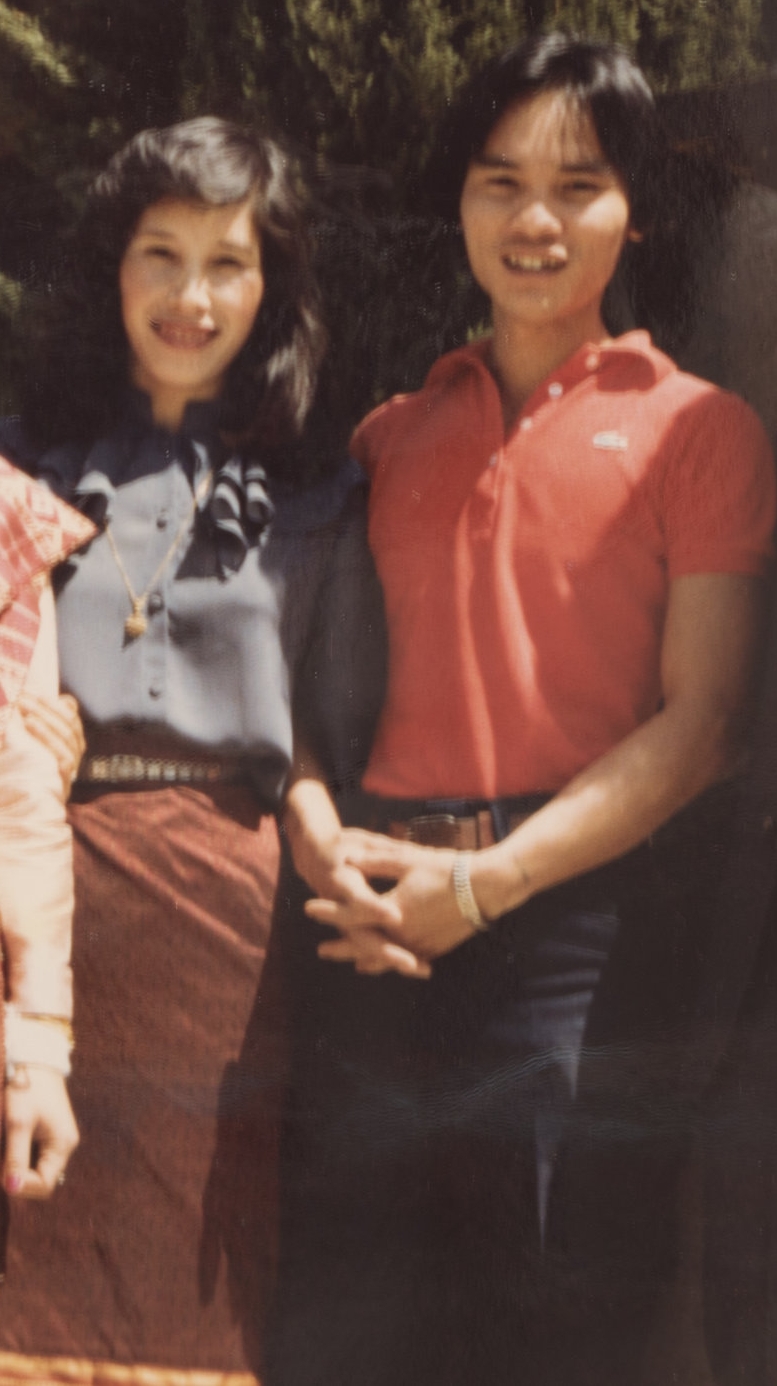

My parents, Prasith and Daeng Silavong, are refugees. It’s difficult to tell if you don’t know them or anything about Laos, their home country. Americans see an old Asian couple and likely assume they are Chinese or Japanese. This assumption includes the “model minority” stereotype, which is unfairly used, typically by the political right, to shame African Americans.

This prejudice, which has been a selling point in news articles, also harms other Asians. By lumping south and southeast Asian ethnicities into a single census category, real problems with economic inequality, poverty and discrimination can easily be ignored or dismissed by society.

Laotians like my parents came to America at a disadvantage. They didn’t speak English, nor could they pick their careers back up because their credentials were left behind. My mother taught science in Laos but without a teacher’s certification and English proficiency she looked for work elsewhere. My dad’s skills were translatable for manufacturing but he started off at minimum wage.

My parents and their friends could stave off homelessness because they worked as a community. If someone heard about a job opening, the everyone heard about it almost right away. Everyone grew up in poverty so they didn’t have the material appetites or American attitudes toward economic status. And if someone needed help, everyone pitched in either money or manual labor. They worked hard because they didn’t have a choice.

It’s even hard for me to believe they’re refugees. I grew up knowing nothing about the Indochina Wars, or the Indochina Refugee Crisis. My parents never sat me down and told me about their lives and escape from Laos. They would scarcely mention something about their past, but I couldn’t appreciate the significance at the time.

News and entertainment media told stories about Vietnam and the anti-war movement in the U.S.; the struggle of soldiers transitioning to civilian life; the moral critique of American intervention that focused on American soldiers’ lives but never about the lives of innocent villagers in a foreign land who didn’t ask for war; every story was American centric. But there were no stories about the lives of Lao villages bordering Vietnam.

There wasn’t a Hollywood movie based on the covert air war in Laos, where U.S. planes bombed villages, destroying rice fields and killing farmers and whole families. There were few stories that told Americans about the horrific deeds done in their name, and how it affected the lives of poverty stricken rice farmers going about their day.

Instead, politicians and the Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon administrations justified their executive actions as protecting American interests. That interest was preventing the Soviet Union, under Joseph Stalin, from influencing neighboring countries. Because America had to stop communism at any cost, every action was morally just. Hence, why any American media that tackles this dark truth is immediately labeled un-American.

It’s why, on Sept. 6, 2016, Barack Obama pledged $90 million in aid to Laos for removing unexploded cluster bombs that burrowed in the Plain of Jars over 50 years ago, a significant historical site dating back to the Iron Age. Instead of offering an apology for America’s past transgression, one that to this day kills and maims villagers including children, he said, “Whatever the cause, whatever our intentions, war inflicts a terrible toll.”

Since there wasn’t any popular media that told the Lao story, I went and searched for it. Most of the history written for this website is from “A History of Laos” by Martin Stuart-Fox and “Voice from the Plain of Jars: Life Under an Air War” by the late Fred Branfman.

Stuart-Fox is a retired Australian professor and journalist who’s written mainly about Laos. Branfman lived and worked in Laos as an educational advisor beginning in 1967. Two years later he learned about the air war waged on villagers living in the Plain of Jars and was compelled to tell their story to the American public. He was an anti-war activist.

This is a personal story, so you can take it for what it is. But the duty of a journalist is to give voice to the voiceless, shine the light of truth into the darkness, and comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Journalism is publishing a story someone with power doesn’t want published.